How do you capture the interest of researchers all over the country in 140 characters or less? Danielle Winter ‘18, a senior majoring in biological engineering, would be happy to demonstrate.

As an incoming freshman Park Scholar, Winter had an interest in science and the environment that had been focused on stormwater through an internship with the Stormwater and Erosion Control Department in her hometown of Winston-Salem, NC. To further develop her knowledge, she applied to be a research assistant at the urging of her professor, thus beginning what would turn into a four year endeavor into stream restoration and water treatment. At first, she was helping volunteers get to the field sites, cleaning bottles, and helping with general tasks. But one year later, as the doctoral student leading this multiyear project was leaving the lab, it was Winter, now a sophomore, who would step up to finish monitoring the site.

“We have about 5 years of funding to monitor a stream restoration from start to finish,” Winter said. “She monitored the preliminary phase, while I monitored the restoration itself. In stripping away the soil, you effectively sterilize the ecosystem to perform restoration. A lot of the water quality benefits we get from a natural system are completely eliminated.”

According to Winter, in the 20 to 30 years scientists have been restoring streams, no one else has tried to quantify what she and her team have been monitoring.

“This project is trying to see how much a stream restoration can improve water quality. We kind of assume it works based on ecological principles. Less than 10 percent of all projects are assessed, and less than 4 percent [of researchers] look at what the stream is like before restoration.”

Winter’s lab has had an up close view of stream restoration and has gained a reputation for its high resolution water quality monitoring. While most labs work on a schedule of daily or even weekly measuring, NC State’s lab measures in 15 minute increments, which Winter says is revolutionary for the industry. The amount of data she and her peers have collected is immense and daunting. She anticipates that her upcoming doctoral work will encapsulate almost 5 years of these datasets. Her hope is to develop a modeling software package for contractors to use so that processing this information is more manageable. One of her challenges will be approaching this task from a viewpoint of practical application as well as research purposes.

“It can be hard to realize that I spent 10 months training on this equipment. Of course it seems easy [to me], but I have to be able to train people in one to two days.”

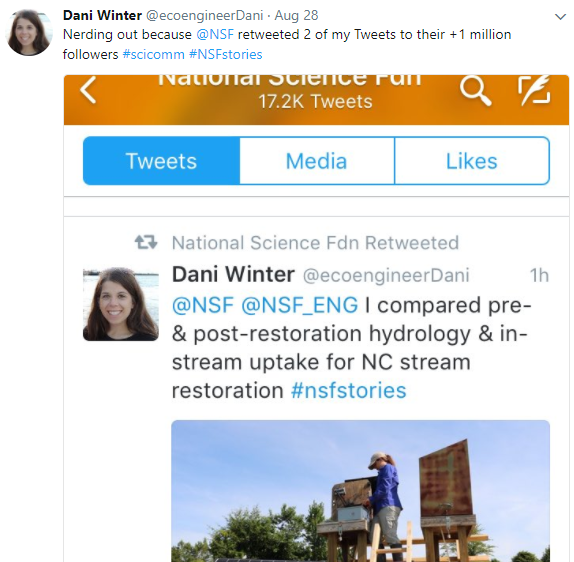

But Winter is no stranger to making her work accessible. Inspired by her stream restoration research, Winter has developed a new stormwater BMP (or “Best Management Practice”) called a Floating Island, which she promotes and tracks via two twitter accounts. Winter and her research team have raised close to $25,000 by writing grants to fulfill their dream of creating their own floating islands on campus. They received a grant from the NCSU Sustainability Fund, which provides grants to students for environmental changes on campus, to pay for their initial materials. Funding through North Carolina Sea Grant paid for testing costs.

Winter says, “It’s great seeing my granting agencies retweet my work. [Twitter] helps me keep track of what I’m doing. It helps as I’m looking for grad school advisors. I’ve had people at conferences come up to me and say, ‘I know you from somewhere… Oh yeah! I know you from Twitter!’ The research Twitter community is very small in each discipline, which really helps in making connections.”

The “island” simulates that of a naturally occurring wetland. Using a geotextile (only developed by two manufacturers in the world) that floats on an untreated wet pond, plants grow and their roots become submerged into the water. The plant uptake and roots act as a filter, essentially treating this previously untreated water.

“If we can prove that floating wetlands are inexpensive and easy to maintain and do make a difference, then hopefully we can make a big impact,” Winter says.

Winter describes herself as a “hands-on person” who loves being outdoors. She says fieldwork has become a great outlet for her. This type of learning changed the way she viewed research and created a multidisciplinary approach to science, due in part to her involvement with the Park Scholarships program. Her Park Faculty Mentor is the extension leader for her department and she says he immediately got the impression from her personality that extension would be a good fit for her.

Winter is excited about the many opportunities her project presents for collaboration. “I teach a College of Engineering summer camp workshop, and it’s terrific bringing in high school students. One student wrote us to say, ‘I want to bring these to my town; can you give me information?’ We bring faculty in from around the country and give them tours. I have a Boy Scout helping me later this week trying to earn his Conservation Badge. We’ve had the Graduate Student Association helping us and, right now, we’re creating a citizen science project. We are hoping that, since our pond is near [on-campus apartment complex] Wolf Village, if students are walking past [and] see wildlife, they’ll tweet at us.”

Visitors to NC State can find Winter’s floating islands on Centennial Campus at Oval Drive and on Main Campus at Wolf Village. Follow her research progress at @ncstate_FIs and @ecoengineerDani.

post by Lauren Caddick

published 2017.09.01